Image from The Exeter DVD Ed. Bernard Muir, Software Nicholas Kennedy, which all good libraries should own.

Tomorrow, I travel to D.C. at the kind invitation of George Washington University's Medieval and Early Modern Studies Institute (thanks for the invite, JJC!) to give a talk about reading Anglo-Saxon poetry adjacent to 20th and 21st century poetry. My talk builds from recent investigations into the way 20th century poets adapted Anglo-Saxon poetry, and argues for adjacent readings of poetry from the two periods; I explore the importance of what is "contemporary to the acting-on-you of the poem," to use a phrase from Charles Olson I thought I'd post a couple of fragments from the talk below, slightly adapted for this blog.

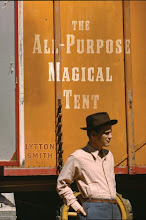

I'll also be reading poems from my debut collection of poems, The All-Purpose Magical Tent, out now from Nightboat Books.

An open, adaptive tendency towards Old English is evident in British poet Geoffrey Hill’s contemporary-Anglo-Saxon poems, especially his 1971 book Mercian Hymns. Here, he turns to Anglo-Saxon poetics—the way poetry is formed—as well as to Anglo-Saxon content. Nicholas Howe has elegantly noted, in a 1998 essay titled “Praise and Lament: The Afterlife of Old English Poetry in Auden, Hill, and Gunn” that Hill’s Mercian Hymns look and feel like prose poems, that hybrid genre often described as Baudelaire’s invention, until one reads them as an Anglo-Saxonist, as works written from left margin to right margin but with a lineation “fixed by internal metrical features rather than by layout on a page” (303). To do so reveals “lines” divided into two halves, with three beats to each half. Hill is not trying to do exactly what the Anglo-Saxon scops did, and carry the typical four beat alliterative poetic line over from the 9th century. Instead, he is drawing on the heft and heave of the Anglo-Saxon poetry, its singular sonics. By doing so, Hill teaches us something both about his own project and about the Anglo-Saxon “Mercian Hymns” he read in Sweet’s Anglo-Saxon Reader: he makes flexible the template by which we approach and sometimes mistake Anglo-Saxon prosody and poetics. The 20th century is just as able and liable to inform the Anglo-Saxon as the other way round, a process succinctly described by Nicholas Howe, with a nod to poet Thomas Gunn, as the way 20th century poets “loosened and revised Old English poetics” (305). These poets’ forays into Anglo-Saxon were not thievish mining expeditions to extract raw materials for re-use in the 20th and 21st century. Instead, they can usefully discover Anglo-Saxon poetics for us, the current readers of a still-present poetry.

***

The multi-directionality of Spring and All might strike readers of 20th century poetry as disruptive, but it is familiar to Anglo-Saxonists. Beowulf is a poem all about re-telling stories and looking back to past events; its structure is, as Michael Lapidge has argued, retroactive, leading readers to move backwards as well as forwards as we assemble meaning. The famous opening phrase of “The Wanderer,” Oft him anhaga “often the solitary one,” is echoed folios later in the Exeter Anthology by the first phrase of Riddle 5, Ic eom anhaga, “I am solitary.” Where “The Wanderer” advises its audience to seek frofre to fæder on heofonum, “consolation with the father in heaven,” the speaker of Riddle 5 frofre ne wene, “does not expect consolation.” The poems are not companion pieces, nor do they explicate one another, but they self-consciously suggest the possibility of reading across the Exeter Anthology, yet one more way of seeing it, as Muir does, as a carefully organized book, one that comments on its own textual practices. The last phrase of "Wulf and Eadwacer," the poem preceding Riddle 1 in the Anthology contains the word giedd, song or riddle, situating riddlic practice outside of the riddle section, and questioning what it means to call a text a riddle. Spring and All, with its interruption of normative, unidirectional reading practices, offers us a way to think flexibly about the recursions and echoes we encounter within the Exeter Anthology.