Monday, April 21, 2008

Garfield Plus Garfield Plus Nonnarrative

Anyway, an illustration to make you smile, courtesy of GB (thanks!) who, like many of my friends, and me, are hard at work in the library. This site stitches together random Garfield panels stitched with delightfully nonnarrative results. You can generate your own! Go here!

Saturday, April 19, 2008

Aye-Aye? Eye, Ye? E-i-o?

lighght

for Paris Review , thus earning him (and it) $500 of National Endowment for the Arts funding and inviting the fury of Senator Jesse Helms and others (almost all Republicans, interestingly) at the use of government funding for something Helms didn't think was a poem and certainly thought was misspelled. (The reasons it's not misspelled I hope to post on another day. But I'm still writing that darn essay and can't stop long today.)

This post isn't really about that poem, but the fact that, in the context of Aram Saroyan's eponymous first book, the poem is in a sequence between

eyeye

and

morni,ng

I never knew that until I was reading his Complete Minimal Poems today. I feel like more people should know that. Because while there's something so delicious and open about "lighght," I'm thrilled to think of it in sequence with these two other words, to construct such phrases as "eyeye lighght morni,ng" and hear "a light mourning" or "I like morning."

I'm looking forward to spending much more time with his book. Another favorite is crickets, which I can't reproduce here. Go out and find it!

PS: Ugly Duckling Presse do amazing year-long subscription deals. $80 for a year of amazing poetry in the most beautiful editions, books that make owning a book really worthwhile and essential. I had one last year and didn't get one this year. I regret that. I'm getting me one again for next season. I recommend it.

Thursday, April 17, 2008

Are You Notable?

To simplify, Wikipedia believes that the publication of two poetry books is not a notable act and therefore doesn't qualify for a bio.

Wikipdia has hardly a single bio for a living poet. I'd guess that there's not one for a poet born after 1960. [EDIT: I found one today for Jeff Clark. So there may be a few. But too few.] John Gallaher challenges us each to post one. Go do it now. He's claimed Martha Ronk. Click here and scroll down. [Clark's is a good model to follow.]

For an encyclopedia, especially one claiming to be a "free Encyclopedia which anyone can edit" and which has as its "primary role [...] to write articles that cover existing knowledge; this means that people of all ages and cultural and social backgrounds can write Wikipedia articles" this is stunning and depressing.

What makes it worse is that the commenters voting on whether a poet's bio stays or goes base their votes on whether the poet is published by a mainstream press, or whether he/she has won a mainstream award.

There are so many problems with this. Some of them are ours, as poets and readers of poetry, to deal with: to inform people better about our poetry, about the poetry we love, about the situations in which poetry comes to be published, whether as a chapbook, a webzine, an act of graffiti. Many of these problems relate to Wikipedia, however, indicating an elitism, a narrow-mindedness, and an ignorance that I believe don't reflect that views of the multitude of users and contributors to Wikipedia.

I'm writing this because I believe poetry is notable. I believe a book of poems is notable. I believe that part of being a poet is pointing out how poetry affects us today, and how we should take note. For Wikipedia to tell me poetry isn't notable is beyond belief. Please take a moment to post a bio for a contemporary poet.

A Reading: Thursday April 24th, 440 Gallery

JOIN US FOR A READING AT PARK SLOPE’S 440 GALLERY!

WHEN: Thursday, April 24th from 7-9 pm

WHERE: 440 Gallery, 440 Sixth Avenue (at 9th St., F to 7th Ave.)

CONTACT: Brooke Shaffner at brshaffner@hotmail.com

Admission Free

WHO:

Carey McHugh’s chapbook, Original Instructions for the Perfect Preservation of Birds &c., was selected by Rae Armantrout for the Poetry Society of America’s New York Chapbook Fellowship. Her poems have appeared in Smartish Pace, Boston Review, Denver Quarterly and elsewhere. She currently lives in Manhattan and teaches writing in the Bronx.

Karen Russell's first collection of short stories, St. Lucy's Home for Girls Raised by Wolves, was named a Best Book of 2006 by the Chicago Tribune, the San Francisco Chronicle, and the Los Angeles Times; in 2007 she was featured in Granta's Best of the Young American Novelists and in The Best American Short Stories. She lives in New York City where she is working on another story collection and a novel about a family of alligator wrestlers, Swamplandia!.

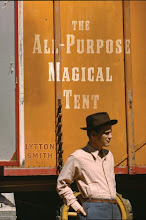

Lytton Smith grew up in Galleywood, England and now lives in New York City, where he studies Anglo-Saxon, travel, and poetics. A chapbook, Monster Theory, was selected by Kevin Young for a New York Chapbook Fellowship and was published this month by the Poetry Society of America. His book, The All-Purpose Magical Tent, won the Nighboat Poetry Prize, judged by Terrance Hayes, and is forthcoming from Nightboat Books in March 2009.

Scott Snyder's collection of stories, Voodoo Heart, was published in 2007 by the Dial Press. He teaches at Columbia University and Sarah Lawrence College and lives on Long Island with his wife, Jeanie, and their son, Jack Presley. He's currently at work on a novel to be published by Dial in 2009.

Todd Erickson, April’s featured artist, will present a talk on his current show, Light, which focuses on his Park Slope backyard. As an environmental artist, his previous installations have documented ecosystems fromFire Island to the Gowanus Canal. Born and raised on Long Island, he received a BFA from Parsons School of Design in 1999, a Certificate in Horticulture from the Brooklyn Botanic Gardens in 2007, and has participated in two artist residencies in Hokkaido, Japan. Todd is currently weaving his artistic practice, garden design sensibilities and knowledge in horticulture into a small business called L.O.G., Leaves of Green.

About 440 Gallery: Park Slope’s only artist-run gallery, a jewel box space offering an alternative venue for Brooklyn artists. 440 Gallery seeks to present surprising, unexpected art to the community through exhibitions, talks, readings and events centered around direct contact with the artist. Open Thursdays and Fridays from 4-7 pm, and Saturdays and Sundays from 12-6 pm, or by appointment.

Tuesday, April 15, 2008

Heartened (finally!)

Something Silliman had to say today, however, made me need to post. He'd expected to find many books that simply weren't competent among the 150 books he's been sent. In reality, he found 5. Setting aside those books that might prove amazing on re-reading but that he didn't "get" first time, and those that lack ambition (a good number), and those where he can't judge impartially (hurrah for making this decision), he writes that he has 70 left.

That there are at least seventy books worthy of such attention in any one year’s crop – not to mention those other volumes I held out on the basis of my relationship with their authors and those volumes that never got submitted – probably is the best assessment of the quality of writing that is taking place at this very moment. It’s really a stunning realization. At least it stunned me.Ever since I got to the U.S. four and a bit years ago, I've had many people, usually poets, tell me how terrible contemporary poetry is. That simply isn't true: there's a wealth of great poetry out there, with huge ambition, and if we devoted our time to finding it and then telling other people about it, more people would be reading poetry. The tired reiteration that modern poetry isn't any good not only indicates a lack of engagement with what's out there (and yes, there is a distribution issue to address, but the blogs do such a great job talking up a range of books that it is no longer that hard to find something) but also does massive damage to the chances of occasional readers of poetry picking up a book.

I'm going to try to recommend at least one book of poetry a week on this blog, and to mention as many poets and poems as I can. In the meantime, one book Silliman must be considering and that I dearly loved is Paige Ackerson-Kiely's In No One's Land which I reviewed here. There's a lot of great books out there, many of which I didn't read, but among the many I read, this is a strong contender, methinks.

1000 balloons = 7000 rockets

Signs around campus starkly read "1000 balloons = 7000 rockets."

My first thoughts turned to the war in Iraq, though sadly there are so many conflicts using what I feel it's accurate to call weapons of mass destruction (not only the military/government/mainstream media gets to define that term) that the statistic could refer to many places in the world. It does in fact refer to the Gaza strip: on April 9th the Candanian Chronicle-Herald reported, deep in a story on the visit of a Canadian-Israel Committee to the Gaza Strip, that "Since the Israelis pulled out of Gaza, there have been over 7,000 rockets sent from Gaza landing around and in Sderot" (according to committee member Michael Zatzman).

Here's not the place to debate why it takes a local story - visitors from Canada, or x untouched place, under fire in a zone where residents are regularly under fire - for the media to pay attention; after all, that the story is news is worth focussing on.

So too are the 1,000 red balloons on campus, and the equation accompanying them. The equals sign reads to me as a question mark and then as a not-equals sign, the gap in number of balloons and number of rockets an implication that, quite aside from partisan affiliations involved with the issue, nothing can stand in for the current of rockets on the Gaza Strip.

The balloons do act as a stand-in though, bringing some version of the idea of rockets to a community which has many strong ties to the area and many members who, like me, have never been to the area and whose only affiliation with it relates to friends, academic study, and media reports. A bright and visual presence on campus, the balloons are also fragile and temporary objects, bound to deflate, fly loose, or burst.

Mapping these three possibilities back onto the rockets brings home one point of the presence of the balloons on campus. The deflated balloons are perhaps no longer a pleasant sight, but they are in a sense disarmed, dead. Those that fly away leave their intended target (the campus community) but their lack of trajectory diverges from the directed flight of rockets. It is only the bursting balloon that echoes the rocket, leading passers-by to stop and look before they continue to pass-by. The continuing to pass-by is, of course, not possible for those who are the advertent or inadvertent targets of rockets.

The balloons then, lead to pause, which sets up the possibility of our acting differently, of not-passing-by, of changing direction. They also attempt to convert, symbolically, the rockets into something safer, something no more dangerous than a loud noise and fragmented rubber. Air escaping.

I'm left wondering what effect they have. It is not enough to write this, and it is not enough because too often it seems enough to write something, to draw attention to it. Is the failure of the media as a fourth estate the continuing direction of attention to events that should be reacted to, rather than the directing of their and our own (written) efforts towards some form of action?

(I'm reminded of a lingering image from Simon Armitage's book-poem Killing Time which reimagines the Columbine shootings as the gifting of unexpected flowers to various students. The effect is haunting, in part because the flowers do not lessen the devastation of the event. The substitution makes what happens seem at once arbitrary and causal, which is pretty much how Aristotle defined tragedy. I'll post an excerpt when I get my copy of the Armitage back from the friend who I've loaned it to.)

Sunday, April 13, 2008

Life Flickring By, Library of Congress Style

I've had a couple of folks ask me where it's from. The Library of Congress has a Flickr photostream, including a set of over 1600 colour photographs from the 1930s and 1940s. To quote the LoC's introductory material:

These vivid color photos from the Great Depression and World War II capture an era generally seen only in black-and-white. Photographers working for the United States Farm Security Administration (FSA) and later the Office of War Information (OWI) created the images between 1939 and 1944 [...] The FSA/OWI pictures depict life in the United States, including Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands, with a focus on rural areas and farm labor, as well as aspects of World War II mobilization.

The one I chose for this blog is called "At the Vermont state fair, Rutland" and was taken by Jack Delano. Below is another of his, called "Side Show at the Vermont state fair, Rutland" which I almost chose, but in the end I love how our view of the fair ends up being through a trailer, with the blue sky framed against the orange paint. Plus, the guy staring of into the distance in front of trailer fascinates me: it's as if he's looking towards a horizon he might be contemplating walking towards. I wonder if he ever did.

So, lastly, a challenge/opportunity. Poet John Gallaher has in the past posted pictures on his blog and wondered what poems/poets might echo them. I'm keen to see what poems/poets images lead us to, so your challenge is to either write a poem or find a poem that somehow sums up or responds to this image. I'm going to try to post an image a week, and see if we can get some conversation between images and poems new and already written.

Friday, April 11, 2008

Poetry as Canary in Mineshaft?

I will retell your version of loss

in bauxite. The fox holes in the field

are cut clean. Mountains to signify

height, to misrepresent sound.

We panicked then pulled men

black and up like early bindweed.

The huntsman kneeling is unfixed

in a grove of new mint. It was like this.

The quiet of the after-hunt. A sackcloth

calm. After the audible cue, a note

on the mineshaft wall There will be oxygen

enough without speaking—

—Carey McHugh, from the chapbook Original Instructions for the Perfect Preservation of Birds &c (PSA: 2008)

I'm thinking about that poem a lot this week, in part because Bookslut interviewed poet Galway Kinnell the other day:

Kinnell once commented that poetry might be the “canary in the mine-shaft.”

“Of course I was thinking that one of the places and one of the ways of keeping the lovely and precious from dying out would be poetry,” he says today. “I think you could extend that to: A whole culture of a country could be kept alive through poetry. So many, many people write in this country that it’s quite astonishing.”

The original canary-mineshaft-poetry analogy was made in the Cortland Review, from an interview conducted early 2001:

DG: I understand what you're saying. Far more Americans will always know who the baseball players are than who the poets are. Does that discourage you?

GK: What troubles me is a sense that so many things lovely and precious in our world seem to be dying out. Perhaps poetry will be the canary in the mine-shaft warning us of what's to come.

What Carey McHugh's poem does, among many things, is offer us a way of thinking about poetry today that is confined to a tired discourse of the "lovely and precious" or the poet-as-celebrity (do poets want to be known the way baseball players are? Poet Trading Cards anyone? I hope not).

McHugh is able to tell us "It was like this," to give us an account of a disaster (averted?) which we feel in the marrow. She shows us the huntsman "unfixed" while also showing us him "kneeling" and a "grove of new mint." Refusing to romanticize the rural imagery, the way Kinnell seems to want to in his canary analogy, she gets to a deeper loss ("a "version of loss / in bauxite"): that the "panicked" quality of men correlated to "early bindweed" can co-exist with, and thus be forgotten amid, "sackcloth // calm." The challenge the canary in the mineshaft represents is a challenge to not let that happen, to not let the moment go unnoticed, unspoken for.

Like the most rewarding poetry, however, "Still Life with Canary" resists a final description. In content, in imagery, it asks to to notice. It's manner of doing so, though reminds us how easy it is to fail to notice: the miners are "pulled [...] black and up." We expect "back" and up, but don't get it: we get instead the image of them coal-covered, or a comment on the numbers of miners of African-American descent working in white-owned mines (see Alena Hairston's wonderful The Logan Topographies). The men are never quite pulled "back and up" unless we read the word hidden with "black". McHugh forces to the foreground the figures of the miners, and we cannot take their rescue for granted. Even brought up to the surface, to what surface are they brought?

I'd venture that Kinnell's analogy is useful, but not in the way he's presenting it. The canary in the mineshaft is a reminder of present danger, of the subterranean unknown, of human attempts to get resources from below the surface, in the dark and lung-clogging tunnels we head into. That can be one way of talking about poetry, but it isn't "lovely" or Romantic. It's precious precisely because we can't respond only to its beauty: we have to respond to its challenge. That's where McHugh leaves us, unfixed ourselves, always within her poem: There will be oxygen / enough without speaking—.

What we speak is itself precious, resourceful and using up our resources. What we speak and what we breathe come together here, and the uttered word has never been so valuable, so necessary -- nor has it been so vital that we choose our speech carefully. That is what Carey McHugh's poetry lets us experience, and it is an experience I take beyond her poems to the groves of mint and the Olympic torch processions and the current election. If the poem is a refuge from the world - and it can be - it is also a warning that the world is still there waiting.

The cover of Carey McHugh's chapbook, designed by the amazing Gabriele Wilson. Original Instructions will soon be available to purchase here or from her in person when she reads on April 24th at 440 gallery Brooklyn, 7pm (with the fantastic fiction writers Karen Russell and Scott Snyder; I'll be the other poet).

Thursday, April 10, 2008

Judging a Book by its Trailer?

For now, I wanted to draw attention not only to Rebecca's crusade (hurrah) to highlight creative book publicity, but to the idea of book trailers, which seem to take all manner of styles. Given the film learned so much from the printed book, it makes sense that books can take a leaf (so to speak) out of the film industry's playbook (playfilm?). I'm watching with interest to see where this leads, but for now I have a challenge to throw at y'all:

Your mission: suggest a trailer idea for a contemporary book of poems (your own is allowed). If people come up with ideas, I'll see if I can find an enterprising film or visual art type who wants to make it a reality. So get thinking! (I can't promise this will happen, but I'm fairly optimistic. Of course, if anyone out there would want to make a poetry book trailer, and is looking for ideas, do get in touch.)

(An aside: Bruce Andrews, in a seminar yesterday, was lamenting what he saw as the failure of different arts forms in NYC in the 80s to work together; in his view, artists in NYC were so successful in their own field that they didn't have time to really collaborate outside of it, at least in a way that challenged their collaborators to reach new goals. I wonder if that's still true today, and I guess it's not accidental that I'm throwing down this inter-art gauntlet the day after his comments.)

Wednesday, April 9, 2008

Life is Better without Garfield

There is something profound and comforting in that panel of silence and space in which Jon is either a) changing the light bulb in the refrigerator; b) failing to change the light bulb in the refrigerator; c) distracted en route to changing the light bulb in the refrigerator.

I'll take my solace where I can get it, folks.

Click through for your daily dose of garfieldminusgarfield; you can even subscribe to an RSS feed. Nerve.com's Daily Scanner described it, ages ago, as strangely Zen, and I'm inclined to agree.

Tuesday, April 8, 2008

On Susan Howe

1.

Maybe this does not belong here. (To be continued…)

2.

I have been mis-reading Susan Howe—as one is meant to. Thorow becomes Thoreau becomes Thor, row becomes (almost) throw, possibly thorough, possibly through. The text re-reads its authors’ (author + reader+authors read = authors’/author’s) reading & transcribing of a word.

It is in this sense, among others, I think about Howe as a poet of typography and topography: writing the landscape of the page (“The Frames should be exactly / fitted to the paper, the Margins / of which will not per[mit] / of a very deep Rabbit”) thorow writing the particularities (particle-uarities) of words.

3.

“Thus, how do we read what is meant precisely to be read? That is given for not other purpose, and without distraction […]. Wordsome.” Bruce Andrews, “Text & Context,” Paradise & Method: Poetics & Praxis, p. 7.

4.

Susan Howe is a poet and critic. What does this sentence tell me? That she writes poetry and that she writes criticism. In the past, and at times now still, I would have assumed that she is writing two things: poetry, one thing, criticism, one thing. Singularities (as well as My Emily Dickinson and possibly Souls of the Labadie Tract) offers to recategorize them as one thing, as spectrum rather than binary. This is especially true if the term critic is not restricted to the literary: Susan Howe is a critic who reads Lake George, New York. “After I learned to keep out of town, and after the first panic of dislocation had subsided, I moved into the weather’s fluctuation.” I was not expecting what she moved into to be anything other than an alternative to the “cabin off the road to Bolton Landing.” As a critic does, as a poet does, Howe has reconceived the world and most importantly the assembly of the world for me: moved, into, weather’s fluctuation – these I understood, experientially and theoretically, already; their construction, causality, togatherness I had not.

Susan Howe has also been a painter. Susan Howe has also been an assistant stage designer. I want to conclude that Susan Howe has been a painter of stage scenery, to keep her biography’s language in motion as she is keeping language in motion. In motion: unresolved. Possibly exhibiting unreadability. “ ‘Unreadability’ – that which requires new readers and teaches new readings.” Bruce Andrews, “Text & Context,” Paradise & Method: Poetics & Praxis, p. 7.

5. How we read what is meant precisely to be read: a list of substitutions provided by the brain, an interruption somewhere along the page-word-subway car air-eyeball-iris-brain that is the material of the world entering the mind as abstract, or so Aristotle said (in a fashion). The following list to be otherwise called “Single Rarities”:

Mustketsquid. (p. 41). Language of the prairie (p. 36). Weather in history and haven (p. 37).Sigh by sea (p. 22). Token (p. 38). etc.

I sometimes find myself reading Howe for the membrane between the word on the page and the word that could have been on the page, thinking of a membrane—the skin, say—as what conducts rather than what barriers. Catcht (caught, catechized) as I am, in the channels of word-osmosis, reading what I imagine to have been almost on the page, allowing what is on the page to remain there, mistaking what is on the page for what I thought was on the page.

7. (…as promised). This criticism belongs (longs for, but extremely so, the difference between a loved and a beloved) where? Or, in other terms, how do we write a criticism of the new poetics that isn’t in the traditional (read: expected; read: expected by who(m); read: for what group with what traditions?) manner. At what point does Andrews’ criticism become a poem (cf. “Suture”) and Howe’s poem become criticism, since each is shuttling between both stations though I know “Text & Context” as criticism in a way I do not initially know “Suture” as criticism and have to come to know it as such, rethinking what I want for and from criticism and poetry in the process, in process.

In what terms do we want the new poetries (some of which are new only to us, some quite old now, some still newer than newly written poetry in the old models) to be conveyed, especially where the reader is rushed, defensive that this is Poetry (and we must GET poetry, we were told, must PARSE poetry, must LEARN AND ROTE it, LEARN AND ROTE it, must UNDERSTAND, we were told, told wrongly). How much work can the criticism ask of the reader? Or, to put it another way, what is vitally lost when the criticism doesn’t ask of the reader a form of work—a radical reconceiving and reconceptualizing of world that would allow for social, political, economic, spiritual, chronological, historical, etceterical revision—that the poetry itself does?

7. Da capo al fine, but with criticism for poetry, poetry for criticism, critic for poet, poet for critic. (I mean also that the critic must be for, in support of, the poet.)

Monday, April 7, 2008

Left Facing Bird

At 10.15 pm in Rock Creek, Montana, Lucas Farrell, Greg Hill Jr., and Brandon Shimoda wrote to a number of writers, hoping to solicit work within the next four hours for a one-off online journal of contemporary poetry. They received and published work from 100 poets, which can be found at Left Facing Bird

That we are in April, and National Poetry Month, fills me with some lethargy: as much as I love finding new poems and poetry, my inbox is full of too many daily poetry e-mails to read. That said, I have to applaud those behind Left Facing Bird: it's not only a great idea, but a treasure trove of poems and poets that'll last long beyond April. It's going to take a while to read this one, and for that I'm glad.

So pass the link onto anyone you think might like to read a poem (especially if it's someone who wouldn't otherwise read a poem in April!). Recommend one, or tell them to pick at random. They're in for a treat.

Sunday, April 6, 2008

The Bridge

Comments on the film on imdb address the ethical issues in making the film, the question of its success as a documentary, the validity of its suggestion that mental illness plays in suicide, the social narratives created about suicide in Western society, and so on. What struck me about both the film, and the discussions it seems to have generated, is the need for those left behind to have an opinion: not just to bear witness to the end of life but to become a part of the story, perhaps because the act of suicide attempts to end a narrative, often but not always one that has repeated itself too many times before.

The Golden Gate bridge - any bridge - is a desire for connection, for connectivity. We will not be prevented from reaching what is visible to us but separate from us, the bridge insists. Lucy Blakstad's book Bridge: The Architecture of Connection offers a visual and textual consideration not just of how bridges connect, but also how they can sever, and its this idea that lingers most for me after the film. The film The Bridge raises the question of why the Golden Gate is the most popular place for suicide in the world, and the friends of jumpers identify a drama or romanticism that might explain why their loved ones sought the GOlden Gate. One mother describes the bridge as "calling" her son, as "magnet-like." While a single reason for the Golden Gate's appeal must elude us, just as a single explanation for the when, how, and why of suicide must, if we are to avoid simplistic understandings of the complex and variously emotional and rational decision to end one's life, that the Golden Gate is a bridge matters.

The choice of the Golden Gate, often during the light of day, seems to allow the jumpers an accessible means of suicide which is also public, witnessed, verifiable. It aligns anonymity - everyone seems a stranger - and identity - the jumper must be noticed. The bridge offers a possibility of connection, of interacting with people, even as the jumper literally moves away from and out of the possibility of connection, into a quick, unreversible descent. The jumper has always started to cross the bridge and not completed the journey, or resisted the idea that there was a journey to complete. A different definition of "the other side" operates: a religious conviction, sometimes, or the refusal to accept the social murmur that better things await elsewhere. We have built bridges in the expectation that people will want to cross over them, that there must be worth getting to from here. The jumpers from the Golden Gate are a flurry of activity often too fast for the viewer to catch, the camera to capture; they pause the activity of crossing, force us to stop and wonder. Without the camera, this would have gone unremarked by all but a few.

Saturday, April 5, 2008

Treehousing

The current issue (5) of A Public Space has a wonderful illustrated guide by Lucy Begg called (Field] Notes on/from a Treehouse [in Texas]. She describes and illustrates in drawings and photographs the building of a steel treehouse in the Lost Pines area of Texas, on a piece of land belonging to Richard Linklater, near Bastrop TX.

Perhaps my favourite part of the guide is the naming of the treehouse Skylark, and the picture of the wonderfully bearded "hand old-school sign painter" Greg Jones.

I loved the name because it seems to sum up the endeavour exactly: a lark in the treetops, up by the sky. There's another reason for the name, though: chief architect Steve Ross suggested it when the Wordsworth poem "To a Skylark" came into his mind during the project. Ross writes to Linklater that "Wordsworth used the skylark as a metaphor for a more 'fully self realized life'" and recalls that Emerson wrote about the poem (Linklater's treehouse ambitions owe a lot to the Transcendentalists).

It's beautiful to think of Wordsworth, that earth-bound poet always walking, walking, walking, but with his gaze so often to the air, christening an aerial space that collapses sky and ground, a platform 21 feet up in the air around which the tree can continue to grow.

The poem, however, and somewhat pleasingly, isn't Wordsworth's, but was written in Italy in 1820 by Percy Bysshe Shelley. The authorship matters less, I think, that the imaginative possibilities a mis-remembered line suggested to a group working in the woods, eating tacos cooked on off-cut steel sheeting, hauling a structure into the air. But the poem's worth reading, not least because it contains the fabulous address "thou scorner of the ground." I've posted it separately below.

Picture is of the oldest treehouse in the world, a Gothic design at Pitchford Hall Estate, United Kingdom. If anyone has pictures of Linklater's treehouse, let me know.

To a Skylark (Percy Bysshe Shelley)

Hail to thee, blithe Spirit!

Bird thou never wert,

That from heaven, or near it,

Pourest thy full heart

In profuse strains of unpremeditated art.

Higher still and higher

From the earth thou springest

Like a cloud of fire;

The blue deep thou wingest,

And singing still dost soar, and soaring ever singest.

In the golden lightning

Of the sunken sun,

O'er which clouds are bright'ning,

Thou dost float and run,

Like an unbodied joy whose race is just begun.

The pale purple even

Melts around thy flight;

Like a star of heaven

In the broad daylight

Thou art unseen, but yet I hear thy shrill delight -

Keen as are the arrows

Of that silver sphere

Whose intense lamp narrows

In the white dawn clear

Until we hardly see -we feel that it is there.

All the earth and air

With thy voice is loud,

As, when night is bare,

From one lonely cloud

The moon rains out her beams, and heaven is overflowed.

What thou art we know not;

What is most like thee?

From rainbow clouds there flow not

Drops so bright to see

As from thy presence showers a rain of melody.

Like a poet hidden

In the light of thought,

Singing hymns unbidden,

Till the world is wrought

To sympathy with hopes and fears it heeded not:

Like a high-born maiden

In a palace tower,

Soothing her love-laden

Soul in secret hour

With music sweet as love, which overflows her bower:

Like a glow-worm golden

In a dell of dew,

Scattering unbeholden

Its aerial hue

Among the flowers and grass, which screen it from the view:

Like a rose embowered

In its own green leaves,

By warm winds deflowered,

Till the scent it gives

Makes faint with too much sweet these heavy-winged thieves:

Sound of vernal showers

On the twinkling grass,

Rain-awakened flowers,

All that ever was

Joyous, and clear, and fresh, thy music doth surpass.

Teach us, sprite or bird,

What sweet thoughts are thine:

I have never heard

Praise of love or wine

That panted forth a flood of rapture so divine.

Chorus hymeneal

Or triumphal chaunt

Matched with thine would be all

But an empty vaunt -

A thing wherein we feel there is some hidden want.

What objects are the fountains

Of thy happy strain?

What fields, or waves, or mountains?

What shapes of sky or plain?

What love of thine own kind? what ignorance of pain?

With thy clear keen joyance

Languor cannot be:

Shadow of annoyance

Never came near thee:

Thou lovest, but ne'er knew love's sad satiety.

Waking or asleep,

Thou of death must deem

Things more true and deep

Than we mortals dream,

Or how could thy notes flow in such a crystal stream?

We look before and after,

And pine for what is not:

Our sincerest laughter

With some pain is fraught;

Our sweetest songs are those that tell of saddest thought.

Yet if we could scorn

Hate, and pride, and fear;

If we were things born

Not to shed a tear,

I know not how thy joy we ever should come near.

Better than all measures

Of delightful sound,

Better than all treasures

That in books are found,

Thy skill to poet were, thou scorner of the ground!

Teach me half the gladness

That thy brain must know,

Such harmonious madness

From my lips would flow

The world should listen then, as I am listening now!