I will retell your version of loss

in bauxite. The fox holes in the field

are cut clean. Mountains to signify

height, to misrepresent sound.

We panicked then pulled men

black and up like early bindweed.

The huntsman kneeling is unfixed

in a grove of new mint. It was like this.

The quiet of the after-hunt. A sackcloth

calm. After the audible cue, a note

on the mineshaft wall There will be oxygen

enough without speaking—

—Carey McHugh, from the chapbook Original Instructions for the Perfect Preservation of Birds &c (PSA: 2008)

I'm thinking about that poem a lot this week, in part because Bookslut interviewed poet Galway Kinnell the other day:

Kinnell once commented that poetry might be the “canary in the mine-shaft.”

“Of course I was thinking that one of the places and one of the ways of keeping the lovely and precious from dying out would be poetry,” he says today. “I think you could extend that to: A whole culture of a country could be kept alive through poetry. So many, many people write in this country that it’s quite astonishing.”

The original canary-mineshaft-poetry analogy was made in the Cortland Review, from an interview conducted early 2001:

DG: I understand what you're saying. Far more Americans will always know who the baseball players are than who the poets are. Does that discourage you?

GK: What troubles me is a sense that so many things lovely and precious in our world seem to be dying out. Perhaps poetry will be the canary in the mine-shaft warning us of what's to come.

What Carey McHugh's poem does, among many things, is offer us a way of thinking about poetry today that is confined to a tired discourse of the "lovely and precious" or the poet-as-celebrity (do poets want to be known the way baseball players are? Poet Trading Cards anyone? I hope not).

McHugh is able to tell us "It was like this," to give us an account of a disaster (averted?) which we feel in the marrow. She shows us the huntsman "unfixed" while also showing us him "kneeling" and a "grove of new mint." Refusing to romanticize the rural imagery, the way Kinnell seems to want to in his canary analogy, she gets to a deeper loss ("a "version of loss / in bauxite"): that the "panicked" quality of men correlated to "early bindweed" can co-exist with, and thus be forgotten amid, "sackcloth // calm." The challenge the canary in the mineshaft represents is a challenge to not let that happen, to not let the moment go unnoticed, unspoken for.

Like the most rewarding poetry, however, "Still Life with Canary" resists a final description. In content, in imagery, it asks to to notice. It's manner of doing so, though reminds us how easy it is to fail to notice: the miners are "pulled [...] black and up." We expect "back" and up, but don't get it: we get instead the image of them coal-covered, or a comment on the numbers of miners of African-American descent working in white-owned mines (see Alena Hairston's wonderful The Logan Topographies). The men are never quite pulled "back and up" unless we read the word hidden with "black". McHugh forces to the foreground the figures of the miners, and we cannot take their rescue for granted. Even brought up to the surface, to what surface are they brought?

I'd venture that Kinnell's analogy is useful, but not in the way he's presenting it. The canary in the mineshaft is a reminder of present danger, of the subterranean unknown, of human attempts to get resources from below the surface, in the dark and lung-clogging tunnels we head into. That can be one way of talking about poetry, but it isn't "lovely" or Romantic. It's precious precisely because we can't respond only to its beauty: we have to respond to its challenge. That's where McHugh leaves us, unfixed ourselves, always within her poem: There will be oxygen / enough without speaking—.

What we speak is itself precious, resourceful and using up our resources. What we speak and what we breathe come together here, and the uttered word has never been so valuable, so necessary -- nor has it been so vital that we choose our speech carefully. That is what Carey McHugh's poetry lets us experience, and it is an experience I take beyond her poems to the groves of mint and the Olympic torch processions and the current election. If the poem is a refuge from the world - and it can be - it is also a warning that the world is still there waiting.

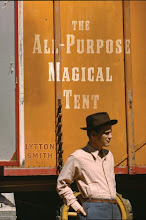

The cover of Carey McHugh's chapbook, designed by the amazing Gabriele Wilson. Original Instructions will soon be available to purchase here or from her in person when she reads on April 24th at 440 gallery Brooklyn, 7pm (with the fantastic fiction writers Karen Russell and Scott Snyder; I'll be the other poet).

No comments:

Post a Comment