In the past week, Jason Guriel, Ron Silliman, and Michael Schiavo have all offered what might be called "negative" reviews of books of poems: reviews that don't flinch from articulating what they see as the flaws of books which have garnered praise and attention. Such reviews might seem to fly in the face of Auden's famous dictum "Criticism will be love, or will not be." Guriel prefaces his own triple-review with an interesting reflection on his process: "Movie critics with whom we disagree are merely wrong; poetry critics (and politicians) go negative." While the movie comparison isn't ideal (I wonder how much negative reviewing there is of independent movies in comparison to mainstream films) Guriel's call for another term - he suggests "necessarily skeptical," admittedly with his tongue slightly in cheek - to describe these types of review is worth attending to.

Part of the problem with negative/positive as terms is that they situate reviewing only as an activity aiming to get us to read or not read a book. Reviewing, though, does much more than that. It develops and articulates the conversation "we" are having about poetry while also broadening who that "we" is. Perhaps few non-poets have read the recent reviews that have caused a stir on the blogs, but we need that to start happening. I've read plenty of theater reviews beyond the number of shows I've been able to see; such reviews, whether they recommend the show or urge me to avoid it, allow me a participation in a conversation about contemporary theatre. We can't read and re-read all the worthy books of poems that come out in any one year - as Ron Silliman's posts on the William Carlos Williams award indicate - which is one of the reasons an articulate and visible review climate, consisting of recommendations as well as hesitations, is necessary. As John Gallaher says "If there were more of a conversation about poetry, and that conversation was something people could find some interest in, then they might start to actually talk about the poetry itself."

Michael Schiavo's review of Matthew Dickman's All-American Poem is especially interesting because it confronts an extremely contemporary book in order to broaden the conversation about it. Copper Canyon's website for the book lists "reviews," four of which are by the judge, two blurbers, and a friend of the author. It is not that some of these "reviewers" are his friends that is problematic; what matters is that their interests and methods do not lie in giving us a complete picture of the book: how does it differ from Frank O'Hara? Does it really mean anything to say "These poems swing with verve and luminosity. They take no prisoners." as Dorianne Laux suggests?

These commenters' partiality - in the sense of being incomplete and of being biased towards, both fine qualities if announced as such, which the description of Tony Hoagland as "judge" does (nowhere does the website admit some of these "reviews" are from the jacket blurbs) - filters down into supposedly objective reviews, like the other two featured excerpts, which are from established venues - Los Angeles Times Review, New Haven Review. As well as using some of the vocabulary the partial blurbers used, these reviews both rely on a mention of Whitman and O'Hara. The conversation about poetry too often develops in this way, by shorthand, the easiest possible ciphers for situating a book. Such ciphers are not only inaccurate, as a glance at Dickman's book shows: they cement the American canon in narrow ways. I long for someone to describe a book in terms of it being "as American as Jose Garcia Villa," and thus to recognize that the description of anything as American must be complex. Michael Schiavo's own review approaches this position as it takes such reviewerly laziness to task: "Name-checking the states of the Republic does not make your poetry Whitmanic. Shoveling pop culture references into sloppy lines does not transform your poems into Frank O’Hara’s." His target is both the poetry and the conversation, and that's what makes his review so useful to us as readers and potential readers of poetry, whether Dickman's book or no. His own work, interestingly, offers a pretty complex version of America, as I get to later.

Reviewing is fundamental to our reading practices, for what we chose to read and not read. The incautious review that relies on shorthand not only risks giving an inaccurate impression of a book but it takes attention away from other books we could be reading: a far worse thing for poetry than a so-called negative review, since the would-be reader who listens to a review and finds that the book is nothing like Walt Whitman might not return to other books of poetry. And so, in this sense, perhaps Auden's dictum still holds: Criticism will be done for the love of poetry, society, of politics, or it will not be done.

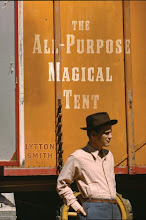

This week on The All-Purpose Magical Tent, I'm going to feature a two-part interview with Michael Schiavo, conducted before his review and addressing in part his own book, which I'd like to suggest is one of the books that fetishizing the Dickman twins' blend of personality and ciphered Americanism could obscure. (A list of five others ends this post; I'd recommend checking out reviews of each to see if they're your cup of tea).

I first began interviewing Michael because I was taken with the means of production of his book. Published via an Espresso Book Machine at Northshire Books in Vermont, complete with a foreword by Douglas Crase, The Mad Song links the production of poetic knowledge - the writing of poems - to the production and distribution of the book itself, an intricate and engaging step that is not fully covered by existing dimensions of Print On Demand, Self-Publishing, the First Book Contest, or the time-honoured and necessary tradition of friends publishing the friends and strangers whose work they admire.

I pitched an interview to Poets and Writers, thinking that they, as the foremost magazine for beginning, emerging, and even established poets, would be keen to feature another dimension of the publishing conversation. They declined, so I decided to run the interview here on Wednesday and Friday. I hope any of you who read it will disseminate it widely as I think it deserves a wide audience. Michael speaks engagingly on The Mad Song, on the methodology of publication, on independent bookstores (he's a bookseller at Northshire), and on questions of American-ness, influence and spirituality.

The other reason I wanted to interview Michael developed once I had begun the process and started reading his book. Formally as well as thematically it engaged and enticed me, leading me to readings and re-readings. Pound wanted us to compose in the sequence of the musical phrase and not the metronome, but Schiavo does both,: the irregular metronome that measures The Mad Song ticks from conditional to imperative, and its hesitancy in remaining at either pole suggest how complex and conflated each position is in the current socio-political arena, and in the historical-mythical America. The Mad Song isn't a unconsidered paean to diaspora, an elegy for a lost past, or a lament for a broken promise of the future, although it put each of these modes into play. What it does is investigate, in its formal methodology - its anaphoric gestures, "incomplete" sentences, unanchored vocalization - and its thematic registers, the challenges and paradoxes of participatory democracy.

The way that The Mad Song enacts such participatory democracy (not to celebrate it only, or to castigate it, but to set that metronome ticking between both positions) is evident from the first paragraph:

Of Bedlam in its prairie pride. Of the roach that winds between the stars, triumphal. Of well-water served in garnet goblets. Of crusted penknife sitting on the pillow in the crib. Of the foxy light July bestows. Of tightwad peace and spendthrift war. Of the ousted governor’s children, especially his eldest, and the way she swings her hips. Of notorious arts and how they make hoi polloi drunk. Of lauren-blue drifts and plumes. Of your vulcanized scent. Of nightly the oceanic barb I must remove from my heart. Of the bison and the owl. Of a country boy, not easy to know.

These sentences pose questions of connection and adjacency: to each other, but also to the worlds and cultural particulars in which they seek to participate. The nod to the epic opener, "of," and the erasure of the familiar "I sing." The gesture to American iconography and the complication of it: how to square "the bison and the owl," how to take the status of the "ousted governer?" The way this paragraph involves the personal is not to sing identity but to complicate it, "a country boy, not easy to know." Amid these recombinant sentences and fragments, where we are mid-stream but unsure if we're missing the source or the end, the question of who we are as selves becomes problematic. The activity of speaking is dynamized within The Mad Song . This book's pronouncements are just there: pronounced, moving between contexts, asking us to speak with and against them. This is the wisdom of the mad song and The Mad Song. As it beats its own, singular drum, it doesn't ask us to follow along, but to join in, keeping a different rhythm if we so choose. That, after all, is where conversation begins.

Check back here Wednesday for Part One, and Friday for Part Two. In the meantime, here's five books which I think articulate Americas in intricate and compelling ways. The links take you to thoughtful reviews.

Quan Barry's Controvertibles

Craig Santos Perez's from Unincorporated Territory

Patrick Rosal's My American Kundiman

Laura Walker's Rimertown: An Atlas

Shanxing Wang's Mad Science in Imperial City (This is my own review.)

Three of these reviews, incidentally, are from The Believer. I wasn't trying to plug the magazine, which I have reviewed for, once (but which also rejected poems of mine having already accepted them, because of internal editorial conflict, so I have mixed feelings). However, it is interesting to note that The Believer , which isn't primarily thought of as a poetry review venue, is featuring reviews of some of the more challenging, ground-breaking, and affecting books of poetry being published in the early 21st century. Good for them.

16 comments:

Would it change your opinion to know that both Shiavo and Dickman were at Breadloaf together, and became friends. Later Shiavo even stayed with Dickman while visiting Austin Texas (in hopes of going to the Michener Center, which he was turned down by)and shortly after ended the friendship? This may explain the almsot sociopathic research and strange hatred for Dickman's work. Would Shiavo think differently if Dickman's book was made by an Espresso Machine as well?

And anyone who makes fun of someone for putting their book out them self in an effort to defend one of the most egregious cases of contest nonsense in the post-foetry era, can suck my nutsack.

One thing I'd really like to see is how Matthew Dickman's All-American Poem is like Walt Whitman's poetry. Because it mentions America? I haven't yet read the book, but I've read about 12 of the poems from it, and I just don't see why someone would want to say that about these poems.

It just seems so odd, and so easy.

Looking back over Schiavo's blog, and my blog, and the pshares blog, I notice that after Schiavo's initial close examination of the book itself, none of the defenses of Dickman have had anthing to say about the work itself. It's all been personal against Schiavo or Dickman. That's an old tactic.

I looked around to see if there were any positive reviews of the book, and there are several, but they're pretty useless as reviews go, and seem mostly just interested in the cult of personality that rises from the content of the poems, asserting some genius or rock and roll star.

This happens a lot with books that assert a version of confessionalism at the center. It seems less to me like Whitman or O'Hara than it does Sharon Olds or the 1970s Robert Lowell.

But again, I've only read about a dozen of the poems.

To the first anonymous commenter: no, it doesn't change my opinion that Schiavo and Dickman have been at Breadloaf together. I'm interested in poetry, not personalities, which is a large part of Schiavo's criticism of All-American Poem and my own of the "reviewers," actual and so-called.

I happen to think that all six books I mentioned in my post, including The Mad Song are more interesting books of poetry than All-American Poem ; I recognize that you and I therefore have aesthetic differences, and that means we get a chance to discuss poetry: hurrah! More of that needs to happen, and a world without thoughtful negative reviews (which I think Schiavo's is) can help contribute to. He close reads poems, which too few reviewers do. He thinks about the context of the work with American and global contexts, in a more informed way than most reviewers.

I'd be keen to hear from you why you love All-American Poem so much. That'd be a comment worth making. As I said above, it is and must be about the poetry, not the poet. I don't care whether any of these authors are lovely people or self-centred or what. When I'm reading the poems, I'm reading the poems, not the poet.

As to the Espresso Book Machine question: I have no idea whether Schiavo would think differently. But I think the means of production can matter in a book, whether it's something like Matchbook Poetry or something like the Espresso Book Machine in conjunction with an amazing bookstore and the particular poetic project of The Mad Song . That's the interesting nexus, and your question essentializes the issue. The mode of production is always about more than just the machine printing the work: Whitman arranging type, not just using a letter press.

John, you've got a good point: the reviewers who are claiming Whitman links seem not to have read their Whitman. There are so many good reviewers out there with more care to explain what they mean by using a name: if there is Whitman there, I'd love these reviewers to tell me how.

Thanks for posting, all. I'm pleased people are thinking about this, whatever view they end up taking.

If we take a look at the start of Hoagland's blurb from the Cop. Canyon website:

Matthew Dickman's all-American poems are the epitome of the pleasure principle; as clever as they are, they refuse to have ulterior intellectual pretensions;

We can see what the real cost of the poetry war is. How else does not having "ulterior intellectual pretensions" become a book's key pleasure? Maybe, and I'm just you know riffing here, but maybe it'd be better if we looked for what's actually good first, rather than calling what "isn't what I hate" good.

-Steve Holt

ljs,

About the poetry, not the poet.

Great.

Fine.

Then why does Shiavo spend SO much time making small personal attacks against Dickman? Is that what we've come to want from a review? Many of his biggest complaints have nothing to do with the poems or the poet. Maybe he should send letters of complaint to Paul Muldoon, the editor of The New Yorker, and Stephen Berg of The American Poetry Review, and a couple to Robert Pinsky who was a judge for the Kate Tufts. The snippy little small minded/hearted tone of his review is terrible and smacks of jealousy, though I am sure he is a contented book seller and happy with his book and god bless him I hope he writes many more. But his review sounded as if Dorothy Parker took a dump, and that big steamy dump decided to write a review of a first book in the 21st century.

And listen, most books of poetry are interesting, to one degree or another. And it is not up to the writer , at all, if the book receives praise or gets attention. Should Shiavo's book have gotten reviewed in, say, the LA Times? Possibly. But that is not up to Shiavo...or Dickman...or any of us.

Poetry.

Not the poet.

But that's Shaivo's big interest.

Why Dickman!!???

WHY NOT US!!!!

Anonymous,

If you've got a problem with the tone of Schiavo review, that's fine, understandable, to be expected given your apparent love for All-American Poem , though you must know you're using the very tactics you claim he's so problematically employing (i.e. deliberately mis-spell his name every time you use it). What you're not doing is talking about poetry.

Laura van den Berg has commented thoughtfully as a counter-voice to Schiavo's tone and argument on Plougshares' blog, and Schiavo commented that she should read the book. All-American Poem does, will, and should have its readers; Tony Hoagland is clearly one of them. Fans of Whitman and O'Hara would be better off reading Alena Hairston and Cal Bedient, I suspect, though of course readers' tastes can be happily inclusive.

There's clearly a lot of passion in your involvement with this issue, but as I said before, it'd be great to hear you be passionate about the poetry, Dickman's, Schiavo's, anyone's, rather than about personality. I really enjoy conversations with those who different tastes than me; I find it informative and enriching, even if I'm not convinced. If we're not close-reading poets and the texts they interact with, we're not doing our job as poets and critics, I fear.

Of Bedlam in its prairie pride. Of the roach that winds between the stars, triumphal. Of well-water served in garnet goblets. Of crusted penknife sitting on the pillow in the crib. Of the foxy light July bestows. Of tightwad peace and spendthrift war. Of the ousted governor’s children, especially his eldest, and the way she swings her hips. Of notorious arts and how they make hoi polloi drunk. Of lauren-blue drifts and plumes. Of your vulcanized scent. Of nightly the oceanic barb I must remove from my heart. Of the bison and the owl. Of a country boy, not easy to know.

. . .

that's your quote to show the merit of Schiavo?

i would venture to predict that most readers are going to (as i do) prefer the Dickmans' verse

to that kind of obscurantist blather—

The Dickmans could have no better advocate than Bill Knott. Though I wonder if Schiavo is part of the CIA conspiracy over at The Paris Review. What does your research show, Bill?

http://billknott.typepad.com/bill_knotts_prose_re_p/2009/01/the-paris-review-poets-the-cia-poets-how-tony-hoaglands-ass-is-saved-daily-by-the-academy-of-american-poets-policy-of-pro.html

Brian McNamara

The Dickmans could have no better advocate than Bill Knott.

... that's got to be a litotes:

a good word from a pariah like me is

k-o-d

(kiss of death)——

seriously: what fool would welcome praise from a fool like me?!

"Brian McNamara",

hunh—

okay i'll remember that name the next time i judge a book contest,

only of course i've never judged a book contest because i've never been asked to judge a book contest, so it's unlikely i'll ever be judging a book contest,

unlike Tony the Hoag i have no contest crown to clap on anyone's head,

yeah watch what you say about T. Hoag because he'll be judging the next plum you apply for,

but i won't——i have no power

to confer any prize/award/grant/position

on anybody——

So Dickman's allowed to profit from all the non-poetry twin/tom cruise/ginsberg tried to make out with me in a borders nonsense, but they can't be criticized for it?

I sign my name,

Steve Holt

I love how the Dickmans and their supporters -- who are obviously these attackers of Schiavo, and childishly refuse to spell his name correctly -- are trying to counter the charge of being immature and devious by being immature and devious through anonymous attacks based on petty personal grievances. Great strategy. Attach your name to a discussion of the poetry and I'll start to take you seriously.

- Robert Casey

Dear Bobbie Cassey,

As Shiavo's boy you do a great job defending his small heart. Keep up the good work.

Yrs,

Anon

This just in: a different take on Schiavo's review:

http://htmlgiant.com/?p=6002

Post a Comment